5.2: Navigating the Functional Anatomy of the Brain

- Page ID

- 12589

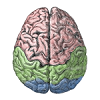

Figure 5.1 shows the "gross" (actually quite beautiful and amazing!) anatomy of the brain. The outer portion is the "wrinkled sheet" (upon which our thoughts rest) of the neocortex, showing all of the major lobes. This is where most of our complex cognitive function occurs, and what we have been focusing on to this point in the text. The rest of the brain lives inside the neocortex, with some important areas shown in the figure. These are generally referred to as subcortical brain areas, and we include some of them in our computational models, including:

- Hippocampus -- this brain area is actually an "ancient" form of cortex called "archicortex", and we'll see in Learning and Memory how it plays a critical role in learning new "everyday" memories about events and facts (called episodic memories).

- Amygdala -- this brain area is important for recognizing emotionally salient stimuli, and alerting the rest of the brain about them. We'll explore it in Motor Control and Reinforcement Learning, where it plays an important role in reinforcing motor (and cognitive) actions based on reward (and punishment).

- Cerebellum -- this massive brain structure contains 1/2 of the neurons in the brain, and plays an important role in motor coordination. It is also active in most cognitive tasks, but understanding exactly what its functional role is in cognition remains somewhat elusive. We'll explore it in Motor Control and Reinforcement Learning.

- Thalamus -- provides the primary pathway for sensory information on its way to the neocortex, and is also likely important for attention, arousal, and other modulatory functions. We'll explore the role of visual thalamus in Perception and Attention and of motor thalamus in Motor Control and Reinforcement Learning.

- Basal Ganglia -- this is a collection of subcortical areas that plays a critical role in Motor Control and Reinforcement Learning, and also in Executive Function. It helps to make the final "Go" call on whether (or not) to execute particular actions that the cortex 'proposes', and whether or not to update cognitive plans in the prefrontal cortex. Its policy for making these choices is learned based on their prior history of reinforcement/punishment.

Figure 5.4 shows the terminology that anatomist's use to talk about different parts of the brain -- it is a good idea to get familiar with these terms -- we'll put them to good use right now.

Figure 5.2 and Figure 5.3 shows more detail on the structure of the neocortex, in terms of Brodmann areas -- these areas were identified by Korbinian Brodmann on the basis of anatomical differences (principally the differences in thickness of different cortical layers, which we covered in the Networks Chapter). We won't refer too much to things at this level of detail, but learning some of these numbers is a good idea for being able to read the primary literature in cognitive neuroscience. Here is a quick overview of the functions of the cortical lobes (Figure 5.5):

- Occipital lobe -- this contains primary visual cortex (V1) (Brodmann's area 17 or BA17), located at the very back tip of the neocortex, and higher-level visual areas that radiate out (forward) from it. Clearly, its main function is in visual processing.

- Temporal lobe -- departing from the occipital lobe, the what pathway of visual processing dives down into inferotemporal cortex (IT), where visual objects are recognized. Meanwhile, superior temporal cortex contains primary auditory cortex (A1), and associated higher-level auditory and language-processing areas. Thus, the temporal lobes (one on each side) are where the visual appearance of objects gets translated into verbal labels (and vice-versa), and also where we learn to read. The most anterior region of the temporal lobes appears to be important for semantic knowledge -- where all your high-level understanding of things like lawyers and government and all that good stuff you learn in school. The medial temporal lobe (MTL) area transitions into the hippocampus, and areas here play an increasingly important role in storing and retrieving memories of life events (episodic memory). When you are doing rote memorization without deeper semantic learning, the MTL and hippocampus are hard at work. Eventually, as you learn things more deeply and systematically, they get encoded in the anterior temporal cortex (and other brain areas too). In summary, the temporal lobes contain a huge amount of the stuff that we are consciously aware of -- facts, events, names, faces, objects, words, etc. One broad characterization is that temporal cortex is good at categorizing the world in myriad ways.

- Parietal lobe -- in contrast to temporal lobe, the parietal lobe is much murkier and subconscious. It is important for encoding spatial locations (i.e., the where pathway, in complement to the IT what pathway), and damage to certain parts of parietal gives rise to the phenomenon of hemispatial neglect -- people just forget about an entire half of space! But its functionality goes well beyond mere spatial locations. It is important for encoding number, mathematics, abstract relationships, and many other "smart" things. At a more down-to-earth level, parietal cortex provides the major pathway where visual information can guide motor actions, leading it to be characterized as the how pathway. It also contains the primary somatosensory cortex (S1), which is important for guiding and informing motor actions as well. In some parts of parietal cortex, neurons serve to translate between different frames of reference, for example converting spatial locations on the body (from somatosensation) to visual coordinates. And visual information can be encoded in terms of the patterns of activity on the retinal (retinotopic coordinates), or head, body, or environment-based reference frames. One broad characterization of parietal cortex is that it is specialized for processing metrical information -- things that vary along a continuum, in direct contrast with the discrete, categorical nature of temporal lobe. A similar distinction is popularly discussed in terms of left vs. right sides of the brain, but the evidence for this in terms of temporal vs. parietal is stronger overall.

- Frontal lobe -- this starts at the posterior end with primary motor cortex (M1), and moving forward, there is a hierarchy of higher-levels of motor control, from low level motor control in M1 and supplementary motor areas (SMA), up to higher-level action sequences and contingent behavior encoded in premotor areas (higher motor areas). Beyond this is the prefrontal cortex (PFC), known as the brain's executive -- this is where all the high-level shots are called -- where your big plans are sorted out and influenced by basic motivations and emotions, to determine what you really should do next. The PFC also has a posterior-anterior organization, with more anterior areas encoding higher-level, longer-term plans and goals. The most anterior area of PFC (the frontal pole) seems to be particularly important for the most abstract, challenging forms of cognitive reasoning -- when you're really trying hard to figure out a puzzle, or sort through those tricky questions on the GRE or an IQ test. The medial and ventral regions of the frontal cortex are particularly important for emotion and motivation -- for example the orbital frontal cortex (OFC) seems to be important for maintaining and manipulating information about how rewarding a given stimulus or possible outcome might be (it receives a strong input from the Amygdala to help it learn and represent this information). The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is important for encoding the consequences of your actions, including the difficulty, uncertainty, or likelihood of failure associated with prospective actions in the current state (it lights up when you look down that double-black diamond run at the ski area!). Both the OFC and the ACC can influence choices via interactions with other frontal motor plan areas, and also via interactions with the basal ganglia. The ventromedial PFC (VMPFC) interacts with a lot of subcortical areas, to control basic bodily functions like heart rate, breathing, and neuromodulatory areas that then influence the brain more broadly (e.g., the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and locus coeruleus (LC), which release dopamine and norepinephrine, both of which have broad effects all over the cortex, but especially back in frontal cortex). The biggest mystery about the frontal lobe is how to understand how it does all of these amazing things, without using terms like "executive", because we're pretty sure you don't have a little guy in a pinstripe suit sitting in there. It is all just neurons!

Comparing and Contrasting Major Brain Areas

| Learning Rules Across the Brain | |||||||

| Learning Signal | Dynamics | ||||||

| Area | Reward | Error | Self Org | Separator | Integrator | Attractor | |

| Basal Ganglia | +++ | --- | --- | ++ | - | --- | |

| Cerebellum | --- | +++ | --- | +++ | --- | --- | |

| Hippocampus | + | + | +++ | +++ | --- | +++ | |

| Neocortex | ++ | +++ | ++ | --- | +++ | +++ | |

Table \(5.1\): Comparison of learning mechanisms and activity/representational dynamics across four primary areas of the brain. +++ means that the area definitely has given property, with fewer +'s indicating less confidence in and/or importance of this feature. --- means that the area definitely does not have the given property, again with fewer -'s indicating lower confidence or importance.

Table \(5.1\) shows a comparison of four major brain areas according to the learning rules and activation dynamics that they employ. The evolutionarily older areas of the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and hippocampus employ a separating form of activation dynamics, meaning that they tend to make even somewhat similar inputs map onto more separated patterns of neural activity within the structure. This is a very conservative, robust strategy akin to "memorizing" specific answers to specific inputs -- it is likely to work OK, even though it is not very efficient, and does not generalize to new situations very well. Each of these structures can be seen as optimizing a different form of learning within this overall separating dynamic. The basal ganglia are specialized for learning on the basis of reward expectations and outcomes. The cerebellum uses a simple yet effective form of error-driven learning (basically the delta rule as discussed in the Learning Chapter). And the hippocampus relies more on hebbian-style self-organizing learning. Thus, the hippocampus is constantly encoding new episodic memories regardless of error or reward (though these can certainly modulate the rate of learning, as indicated by the weaker + signs in the table), while the basal ganglia is learning to select motor actions on the basis of potential reward or lack thereof (and is also a control system for regulating the timing of action selection), while the cerebellum is learning to swiftly perform those motor actions by using error signals generated from differences in the sensory feedback relative to the motor plan. Taken together, these three systems are sufficient to cover the basic needs of an organism to survive and adapt to the environment, at least to some degree.

The hippocampus does introduce one critical innovation beyond what is present in the basal ganglia and cerebellum: it has attractor dynamics. Specifically the recurrent connections between CA3 neurons are important for retrieving previously-encoded memories, via pattern completion as we explored in the Networks Chapter. The price for this innovation is that the balance between excitation and inhibition must be precisely maintained, to prevent epileptic activity dynamics. Indeed, the hippocampus is the single most prevalent source of epileptic activity, in people at least.

Against this backdrop of evolutionarily older systems, the neocortex represents a few important innovations. In terms of activation dynamics, it builds upon the attractor dynamic innovation from the hippocampus (appropriately so, given that hippocampus represents an ancient "proto" cortex), and adds to this a strong ability to develop representations that integrate across experiences to extract generalities, instead of always keeping everything separate all the time. The cost for this integration ability is that the system can now form the wrong kinds of generalizations, which might lead to bad overall behavior. But the advantages apparently outweigh the risks, by giving the system a strong ability to apply previous learning to novel situations. In terms of learning mechanisms, the neocortex employs a solid blend of all three major forms of learning, integrating the best of all the available learning signals into one system.