11.1: The Immune System

- Page ID

- 86877

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Imagine a number that is ten billion times the number of stars in the universe, this is the estimated number of viruses on Earth[1]. Viruses are just one type of microorganism in our environment. Some microorganisms are detrimental to our health making us sick, others are important for our health (beneficial), and others are inconsequential. The microorganisms that cause diseases in humans are called pathogens. In total, there are about 1,400 known species of human pathogens that fall into five groups known as bacteria, virus, fungi, protozoa, and helminths (worms).

Pathogens are found in the air around us, the food we eat, what we drink, and the people and animals we are around, thus we are constantly exposed pathogens. Thankfully our immune system is in a constant battle working to identify the foreign invader (pathogen) and destroy them. This immune system battle is happening right now while you are reading this book!

The main purpose of the immune system is to protect your body from harmful substances, germs and cell changes that could make you ill. With this purpose, the immune system works to:

- fight disease-causing germs (pathogens) like bacteria, viruses, parasites or fungi, and to remove them from the body,

- recognize and neutralize harmful substances from the environment, and

- fight disease-causing changes in the body, such as cancer cells.

Your immune system is made up of two parts that work together to fight off disease. The innate immune system works to constantly find and destroy any foreign invaders, and the adaptive immune system works by remembering previous pathogens and infections to be able to launch a more efficient battle to destroy pathogens upon re-exposure.

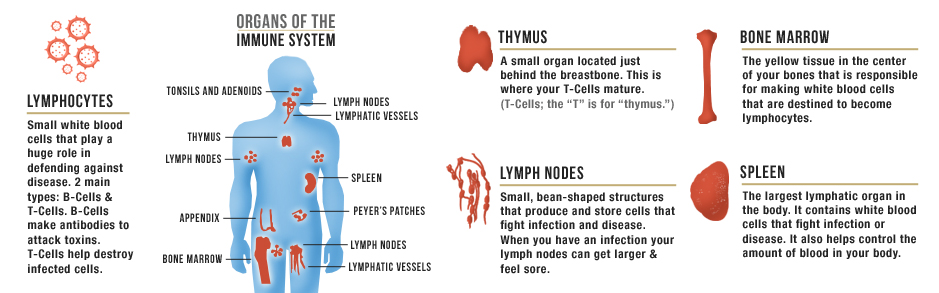

The immune system includes white blood cells, organs, and tissues of the lymph system, such as the thymus, spleen, tonsils, lymph nodes, lymph vessels, and bone marrow. The white blood cells, or immune cells, that help the body fight infections and other diseases include neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and lymphocytes (B cells and T cells).

The immune system is an amazing system of protection, however sometimes it cannot destroy the pathogen and this is when infection or disease occurs, like the Flu, Strep Throat, or a Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD).

Pathogens and Infectious Diseases

The number of viruses and bacteria on earth is staggering[2] and they occupy essentially every environment. For example, a liter of surface seawater typically contains in excess of ten billion bacteria and 100 billion viruses. The vast majority of viruses and bacteria we are exposed to have no negative effect, some can even be beneficial, however a tiny fraction of these can severely affect our health. It is estimated that only about 1,400 of a trillion microbial species are human pathogens. Pathogens are too small to be seen by the naked eye and they live all around us in water, soil, and air.

The agents that cause disease, or pathogens, fall into five groups: viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and helminths (worms). Protozoa and worms are usually grouped together as parasites.

| Virus | Bacteria | Fungi | Parasites/Protozoa |

|

|

|

|

Common Viruses and Mutations

Every year warnings are shared about the annual flu season. The flu is a contagious respiratory illness caused by the influenza viruses that infect the nose, throat, and lungs. It can cause mild to severe illness, and at times can lead to death. Although the flu can be caught year round, in the U.S. it is most common in the Fall and Winter seasons. The flu virus is not the same each year due to what is known as antigenic drift and antigenic shift which essentially indicates that the influenza virus has changed and thus the body will likely react differently to the variations.

Viruses can only replicate if they are absorbed by cells in the body, thus viruses survive based on the ability to continue to infect hosts. In order to continue to infect humans, the virus has to overcome the humans immune systems. Since the immune system can remember past viral infections, viruses mutate and change over time to be able to adapt to their surroundings and more effectively move from host to host. When viruses mutate they evolve into new variants. Virus variants are similar to a family tree with multiple lineages (or closely related groups of variants) and sublineages. Each variant starts with a parent lineage followed by descendant lineages. For example, with COVID-19, the BA.1.1.529 variant is from the Omicron variant.

There is a difference between an endemic, outbreak, epidemic, and pandemic[3]. An endemic condition occurs at a predictable rate among a population. An outbreak corresponds to an unpredicted increase in the number of people presenting a health condition or in the occurrence of cases in a new area. An epidemic is an outbreak that spreads to larger geographic areas. A pandemic is an epidemic that spreads globally.

Pandemics have occurred throughout history impacting the entire world, some of these include:

- Three plagues during the years: 541-543, 1347-1351, and 1885-ongoing.

- Six pandemics of cholera during the years: 1817-1824, 1827-1835, 1839-1856, 1863-1875, 1881-1886, and 1899-1893.

- And numerous flu pandemics: Russian flu from 1889-1893, Spanish flu from 1918-1919, Asian flu from 1957-1959, Hong Kong flu from 1968-1970, SARS from 2002-2003, Swine flu from 2009-2010, MERS from 2015-ongoing, and more recent COVID-19 from 2019-ongoing.

Table List of some of the pandemics that occurred throughout history.

| Pandemic | Timeline | Area of emergence | Pathogen | Vector | Death toll |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athenian Plague | 430-26 B.C. | Ethiopia | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| Antonine Plague | 165-180 | Iraq | Variola virus | Humans | 5 million |

| Justinian Plague | 541-543 | Egypt | Yersinia pestis | Rodents’ associated fleas | 30-50 million |

| Black Death | 1347-1351 | Central Asia | Yersinia pestis | Rodents’ associated fleas | 200 million |

| The Seven Cholera Pandemics | 1817-present | India | Vibrio cholerae | Contaminated water | 40 million |

| Spanish Flu | 1918-1919 | USA | Influenza A (H1N1) | 50 million | |

| Asian Flu | 1957-1958 | China | Influenza A (H2N2) | >1 million | |

| Hong Kong Flu | 1968 | China | Influenza A (H3N2) | 1-4 million | |

| HIV/AIDS | 1981-present | Central Africa | HIV | 36 million | |

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus | 2002-2003 | China | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus | Bats | 774 |

| Swine Flu | 2009-2010 | Mexico | Influenza A (H1N1) | 148000-249000 | |

| Ebola | 2014-2016 | Central Africa | Ebola virus | Unknown | 11000 |

| COVID-19 | 2019- July 2021 (ongoing) | China | SARS-Cov-2 | Unknown | >4 million (ongoing) |

The COVID-19 pandemic was caused by a virus called SARS-CoV-2. Viruses constantly change through mutation and sometimes these mutations result in a new variant of the virus. COVID variations include the Omicron variant and Delta variant, with new variants of the virus expected to occur. The COVOD-19 pandemic is the first global pandemic requiring large-scale responses since the 1918 Spanish flu. As of 2022, COVID-19 is still considered a pandemic and there is still concern of continued spread, sickness, and death.

Pandemics: The Chain of Infection

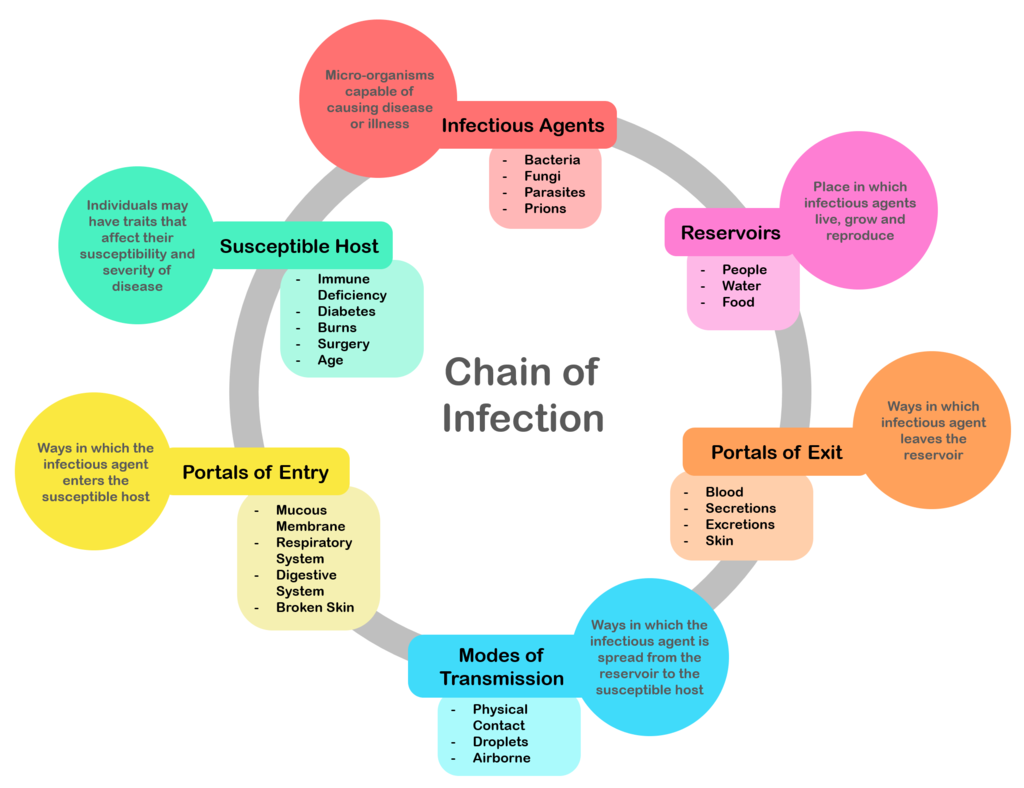

The way in which people become infected with a pathogen is referred to as the Chain of Infection.

The chain of infection begins with the “Infectious Agent.” The infectious agent is a pathogen, a microorganism that is capable of causing disease. There are about 1,400 different pathogens that fall within five main categories of bacteria, virus, fungi, protozoa, and worms.

The infectious agent begins in a “Reservoir.” The reservoir could be another person, an animal, in water, or in food; it is the habitat in which the infectious agent normally lives, grows, and multiplies. The reservoir may or may not be the source from which an agent is transferred to a host. For example, the reservoir of Clostridium botulinum is soil, but the source of most botulism infections is improperly canned food containing C. botulinum spores. Human reservoirs may or may not show the effects of illness. A carrier is a person with inapparent infection who is capable of transmitting the pathogen to others. Asymptomatic or passive or healthy carriers are those who never experience symptoms despite being infected. Carriers commonly transmit disease because they do not realize they are infected, and consequently take no special precautions to prevent transmission.

The infectious agent needs a way to leave the reservoir through a “Portal of Exit.” For a person, this could include breathing out air, or a cut through the skin, touching or rubbing your nose, coughing, sexual intercourse, feces, urine, mucus, or blood.

The infectious agent then needs a “Mode of Transmission” to the new host. The mode of transmission could be direct or indirect. Direct contact and direct spreading of droplets often occur when two people are close together or touching, this could be through hugging, sexual intercourse, or droplets spreading when talking or sneezing when someone is close by. Indirect transmission could occur through the air, on a vehicle such as food or drinks, or transmitted by an insect like a mosquito, flee, or tick.

The infectious agent then needs to a “Portal of Entry” into the new susceptible new host, these are ways the infectious agent could enter the body. The portal of entry must provide access to tissues in which the pathogen can multiply. This might include inhaling the infectious agent into the respiratory system, consuming it through food or drink therefore entering the digestive system, or entering directly into blood or tissues through breaks in the skin.

The final step in the Chain of Infection is when the infectious agent has successfully entered the Susceptible Host. If a pathogen gets past a host’s defenses, it will attempt to infect the host and begin replicating itself; The pathogens must infect a host in order to grow or replicate. However, just because the pathogen has successfully entered the host does not mean they will get infected! This is where the power of the immune system steps in to fight off the infection destroying the infectious agent.

The survival of human pathogens, like viruses, bacteria, and parasites, is dependent upon quickly invading a human, replicating, and efficiently transmitting to others. Pathogens depend on the chain of infection for survival. You can take precautions to break the chain of infection at each step in the chain by doing the following:

- Recognize signs and symptoms of disease in order to get treatment and isolate when needed.

- Wash your hands and/or use hand sanitizer

- Cleaning and disinfect surfaces

- Get treatment from a doctor

- If you have a bacterial infection you need antibiotics. Antibiotics are medicines that fight bacterial infections.

- Avoid touching your face

- Do not cough into your hand, cough into your arm or elbow.

- Use pest control

- Wear personal protective equipment to put a barrier between the portal of exit or entry.

- Use air purifiers to reduce airborne pathogens.

- Properly dispose of waste.

- Drink clean drinking water.

- Follow food safety guidelines.

- Immunizations/vaccines to reduce the susceptibility of the new host.

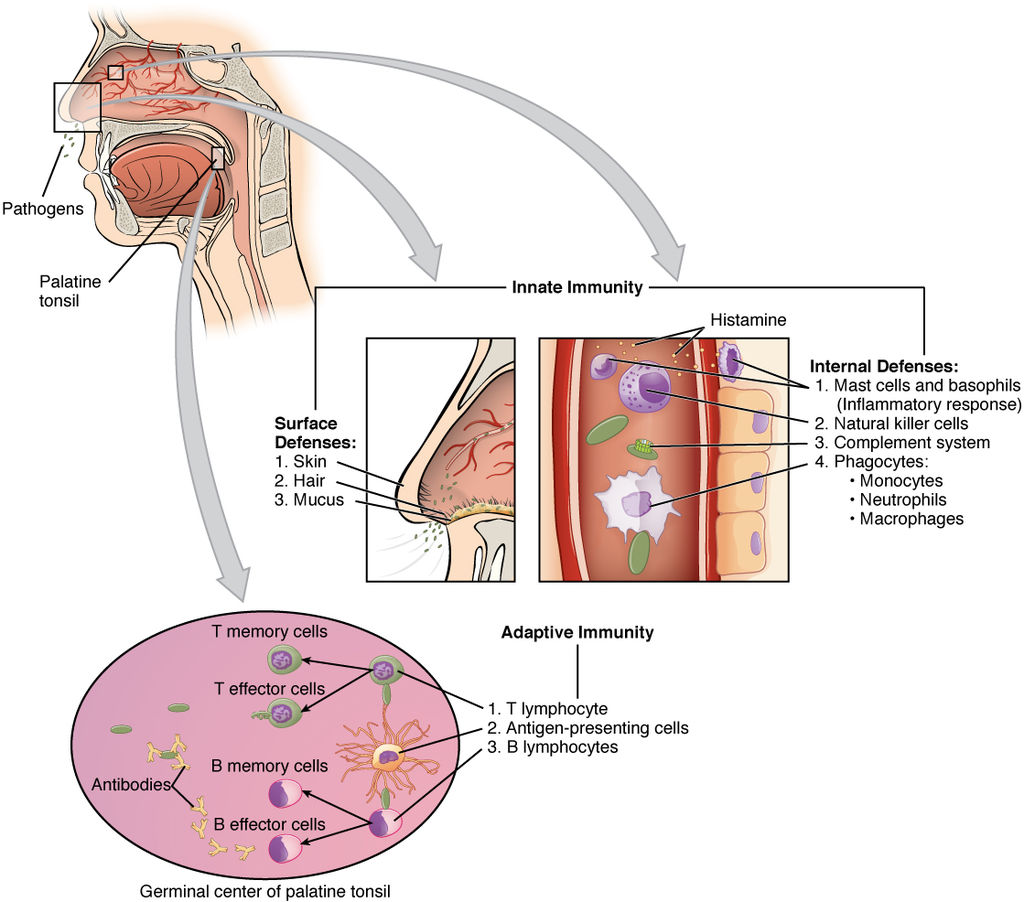

The Immune System Battle

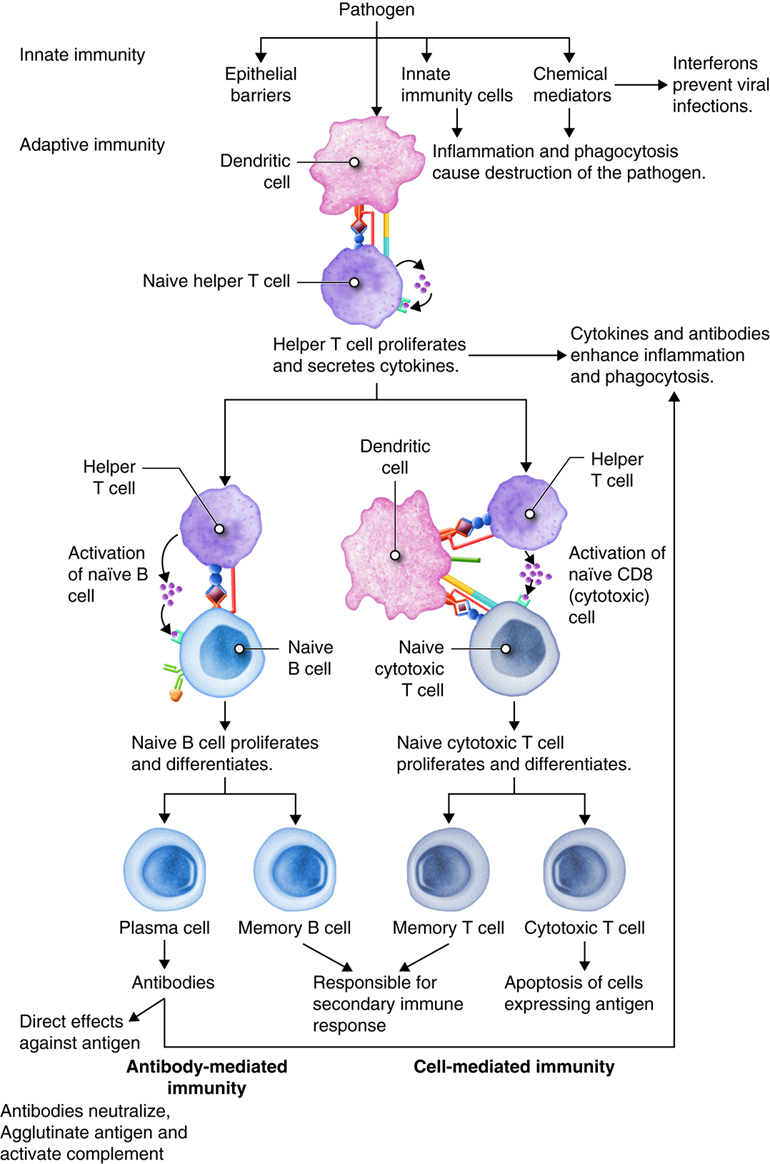

When an infectious agent leaves a reservoir through a portal of exit and finds a mode of transmission, it is then up to the defenses of the new host to try to reduce the chances of infection. This is when the immune system battle commences which includes two main subsystems of the immune system, called the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system. The innate immune system is what you are born with and the adaptive immune system is developed overtime as your body is exposed to pathogens. The innate immune response is always present and attempts to defend against all pathogens rather than focusing on specific ones. Conversely, the adaptive immune response stores information about past infections and mounts pathogen-specific defenses.

The innate immune system includes the bodies physical and chemical barriers along with white blood cells that are always present in the blood and tissues ready to destroy any and all invading pathogens. The adaptive immune system also includes white blood cells, but they are more specialized and ready to destroy specific pathogens.

Immune System: Physical and Chemical Barriers

The first step in the battle against pathogens is to put up a physical barrier against the portal of entry. The largest physical barrier against pathogens is our skin. Skin provides provides both a barrier of entry and a means to destroy pathogens through skin acidity and dryness. The areas of the body that are not covered with skin have alternative methods of defenses using mucus and secretions, like tears in the eyes, wax in the ears, and cilia and mucus in the nose, mouth, and lungs. Despite these barriers, pathogens may enter the body through skin abrasions or punctures, or by collecting on mucosal surfaces in large numbers that overcome the mucus or cilia. Some pathogens have evolved specific mechanisms that allow them to overcome physical and chemical barriers. When pathogens do enter the body, the innate and adaptive immune systems responds.

The Innate and Adaptive Immune System

The main job of the innate immune system is to fight harmful substances and germs that enter the body, for instance through the skin or digestive system. The innate immune system is the rapid response to any invading pathogen, the response is non-specific meaning the same response for any and all pathogens. The adaptive immune system makes antibodies and uses them to specifically fight certain germs that the body has previously come into contact with. This is also known as an “acquired” (learned) or specific immune response. Because the adaptive immune system is constantly learning and adapting, the body can also fight bacteria or viruses that change over time.

Both the innate and the adaptive immune system rely on markers that are on body cells. These markers tell the immune system whether the cell is a human cell that belongs in the body, or whether the cell is foreign. Pathogens have two markers. One marker is non-specific called a Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs), the other markers is specific called an Antigen. Many pathogens share the same PAMPs, however have unique and distinctive antigens; Every invader’s antigenic pattern is unique. The innate immune cells have receptors called Pattern Recognizing Molecules (PRMs) that recognize the PAMP. When the innate cells recognize the PAMP they begin the battle to destroy the foreign invaders. Adaptive immune system cells recognize the specific antigens on the pathogen and launch a battle specifically to destroy that pathogen.

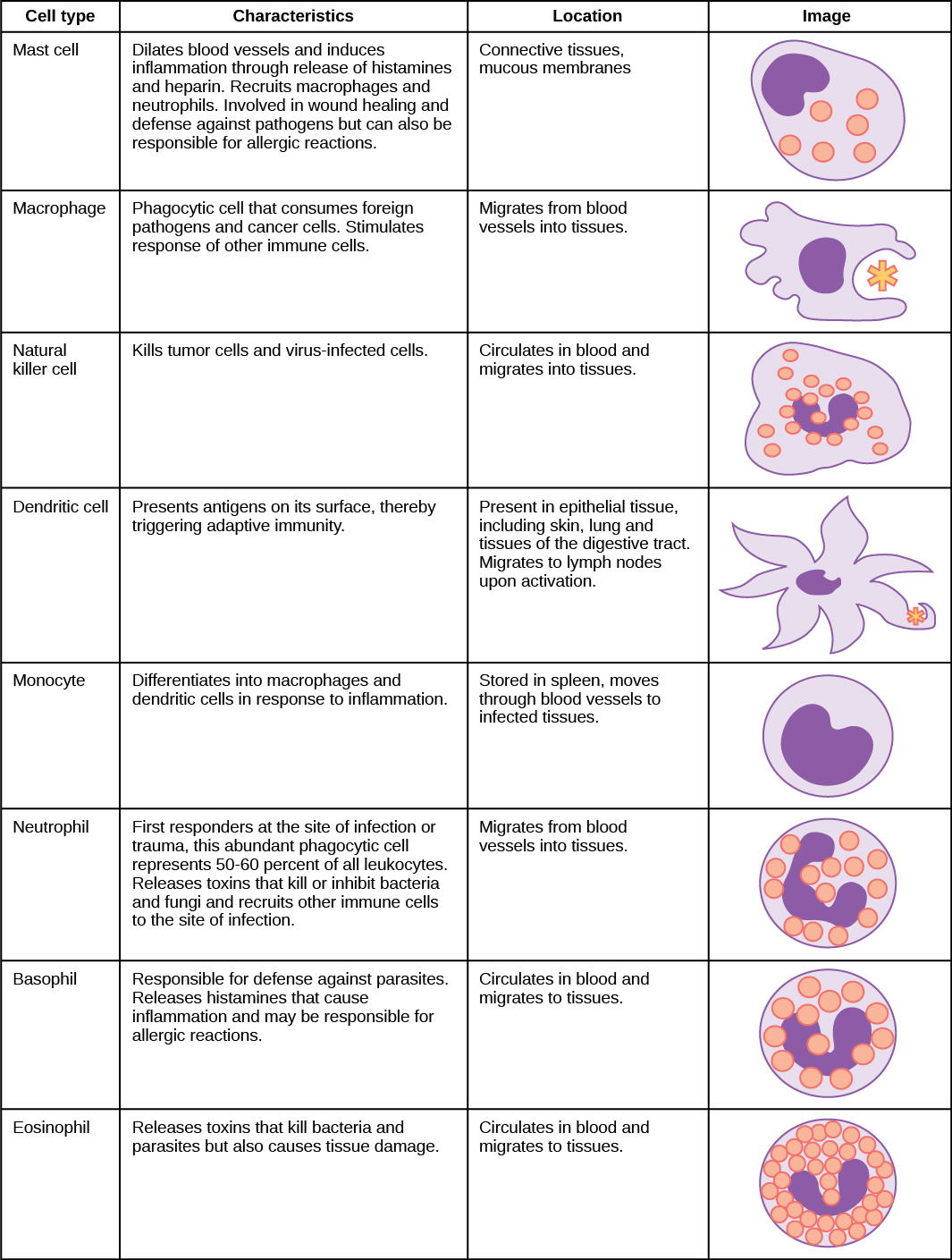

The innate immune system cells are the first to respond, these include the following types of leukocytes: mast cells, macrophages, natural killer cells, dendritic cells, monocytes, neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils (described in Figure 11.?). Cells of the adaptive immune system are classified as lymphocytes (a type of leukocyte) and include two main types: T-cells and B-cells (the letters denote ‘thymus’ and ‘bone marrow’, the tissues where each of these leukocytes mature).

Steps to the The Immune System Battle:

- The cellular immune response begins when a pathogen gets through the bodies physical and chemical barriers.

- If a pathogen gets past the hosts defenses it will attempt to infect the host and begin replicating itself. The subsequent battle between the germs and the body’s immune system will cause the symptoms of illness.

- The first immune cells to respond to the invading pathogen are the innate immune cells: mast cells, macrophages, natural killer cells, dendritic cells, monocytes, neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils. These cells are always ready to fight off pathogens and work hard to destroy the foreign invaders.

- Actions of the innate immune system cells

- Dendritic Cells: Ingest pathogen and help activate the adaptive immune system by presenting their antigen to Helping T-Cells and killer T-Cells.

- Neutrophils: Migrate from the bloodstream to ingest and kill bacteria and fungi and recruit more immune cells.

- Macrophages: Known as the “big eaters”, they ingest pathogens and dead cells and help activate the adaptive immune system by presenting their antigen. They also recruit more immune cells.

- Mast Cells: launch inflammatory response and recruit macrophages and neutrophils.

- Natural Killer cells: Detect and kill tumor or virus infected cells.

- Basophils: Defend against parasites and contribute to inflammatory response.

- Eosinophils: Kill bacteria and parasites.

- The innate immune cells alert the whole body that there is a problem by activating the inflammatory response and initiating the adaptive immune system.

- The inflammatory response brings swelling, pain and higher temperature, which attracts more cells to the site of infection. This means more immune cells join the fight to destroy the pathogen.

- The innate immune cells provide important information to the adaptive immune cells to “train” the adaptive immune cells how to destroy the pathogen.

- Training the adaptive immune cells is done in two ways, by releasing cytokines and displaying the pathogens antigens.

- Cytokines are signals that tell cells what to do and where to go. Your body responds to threats in different ways depending on the cytokine signal released by your immune cells.

- The antigen is displayed when the innate immune cells capture and breakdown the invader.

- Together, the cytokines and antigens train individual adaptive immune cells to recognize and destroy specific patterns of each foreign invader.

- The Adaptive Immune System Cells

- Helper and killer T-Cells are activated after the Dendritic cells engulf the pathogen.

- When the helper T-Cells create B-Cells they are initiating the adaptive immune system.

- Antibodies, B Cells, are then produced that attach to the pathogen.

- The B Cells divide to produce plasma and memory cells.

- If the same pathogen invades again, the memory cells help the immune system activate much quicker.

- When the adaptive cells are “trained” how to fight a specific antigen, they remember how to fight it, thus the next time that this pathogen tries to infect you your adaptive immune cells will remember it and destroy it quickly.

- The ability of the immune system to remember previous pathogens is commonly called adaptive or acquired immunity and is the basis for vaccines.

- However, pathogens really want to live and they can be tricky. Some pathogens, including those that cause flu, strep throat, and malaria, can mutate and change the way they look to your immune system over time by changing their antigen markers thus disguising themselves marking it harder for your immune system to recognize the mutated germs even though you’ve been exposed to them before. This is why you can get sick from flu, strep throat, or COVID multiple times.

Vaccines

It is possible to acquire adaptive immunity naturally or artificially. Natural immunity results from natural exposure to an antigen. For example, someone sneezes the influenza virus into the air and then it is breathed into another person’s nasal passageway. However, artificial immunity refers to deliberately introducing an antigen into an individual to stimulate an immune response, known as a vaccine. Whether you have been introduced to a pathogen naturally or artificially the end result is the same, to develop memory cells to acquire immunity against the pathogen.

If the immune system did not have the ability to remember pathogens then vaccines would not work; vaccines are effective because of memory cells. The mechanism underlying vaccination is that exposure of the adaptive immune system to a small dose of an antigen will produce an initial immune response. More importantly, this small dose of antigen establishes a population of memory T and B cells that will live long-term in the body. When that antigen is encountered again, the immune system is already primed. Upon a subsequent exposure, a more robust and faster response is established and the pathogen is destroyed faster. Vaccines can either prevent or decrease the severity of infections.

There are several different types of vaccines and even more types of vaccines in development. Each type is designed to teach your immune system how to fight off certain kinds of germs—and the serious diseases they cause. When scientists create vaccines, they consider how your immune system responds to the germ, who needs to be vaccinated against the germ, and the best technology or approach to create the vaccine.

| Vaccine Type | Characteristics | Vaccine Protects against |

| Inactivated vaccines |

|

|

| Live-attenuated vaccines |

|

|

| Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines |

|

|

| Subunit, recombinant, polysaccharide, and conjugate vaccines |

|

|

| Toxoid vaccines |

|

|

| Viral vector vaccines |

|

|

| DNA vaccines |

|

In development. No vaccines available yet. |

| Recombinant vector vaccines (platform-based vaccines) |

|

In development. No vaccines available yet. |

There is another way to get temporary immunity and that is called passive immunity, which is when antibodies are provided to the person from a donor recipient, for example from a mother to child as antibodies move across the placenta before birth. Passive immunity is not long-lasting because the individual does not produce memory cells.