18.5: Protein Synthesis and the Genetic Code

- Page ID

- 15386

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- describe the characteristics of the genetic code.

- describe how a protein is synthesized from mRNA.

One of the definitions of a gene is as follows: a segment of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) carrying the code for a specific polypeptide. Each molecule of messenger RNA (mRNA) is a transcribed copy of a gene that is used by a cell for synthesizing a polypeptide chain. If a protein contains two or more different polypeptide chains, each chain is coded by a different gene. We turn now to the question of how the sequence of nucleotides in a molecule of ribonucleic acid (RNA) is translated into an amino acid sequence.

How can a molecule containing just 4 different nucleotides specify the sequence of the 20 amino acids that occur in proteins? If each nucleotide coded for 1 amino acid, then obviously the nucleic acids could code for only 4 amino acids. What if amino acids were coded for by groups of 2 nucleotides? There are 42, or 16, different combinations of 2 nucleotides (AA, AU, AC, AG, UU, and so on). Such a code is more extensive but still not adequate to code for 20 amino acids. However, if the nucleotides are arranged in groups of 3, the number of different possible combinations is 43, or 64. Here we have a code that is extensive enough to direct the synthesis of the primary structure of a protein molecule.

Video: NDSU Virtual Cell Animations project animation "Translation". For more information, see VCell, NDSU(opens in new window) [vcell.ndsu.nodak.edu]

The genetic code can therefore be described as the identification of each group of three nucleotides and its particular amino acid. The sequence of these triplet groups in the mRNA dictates the sequence of the amino acids in the protein. Each individual three-nucleotide coding unit, as we have seen, is called a codon.

Protein synthesis is accomplished by orderly interactions between mRNA and the other ribonucleic acids (transfer RNA [tRNA] and ribosomal RNA [rRNA]), the ribosome, and more than 100 enzymes. The mRNA formed in the nucleus during transcription is transported across the nuclear membrane into the cytoplasm to the ribosomes—carrying with it the genetic instructions. The process in which the information encoded in the mRNA is used to direct the sequencing of amino acids and thus ultimately to synthesize a protein is referred to as translation.

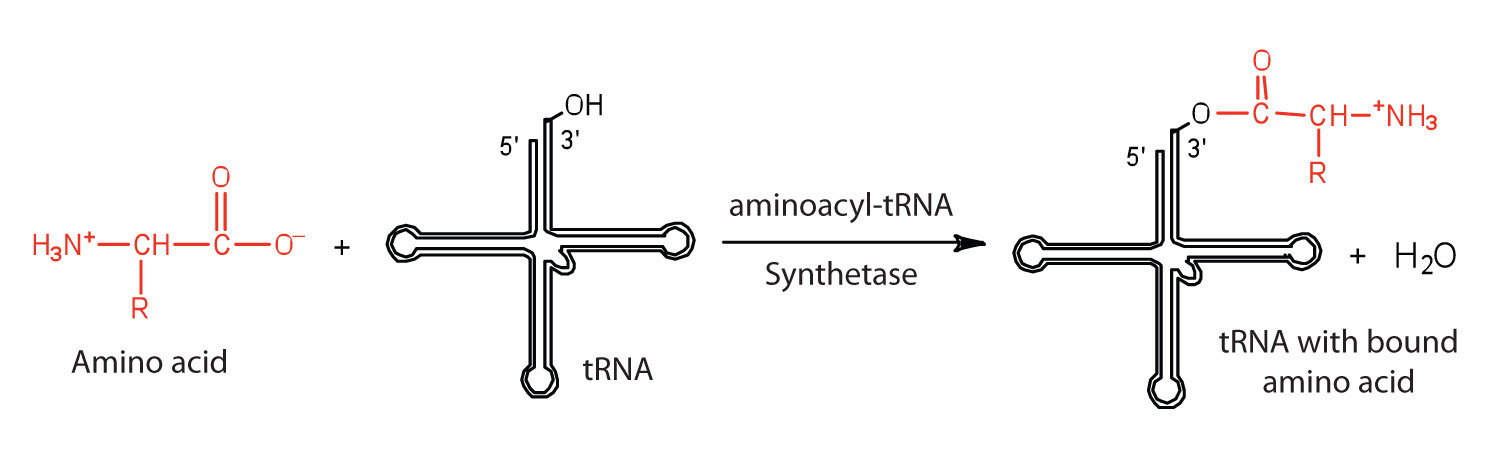

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Binding of an Amino Acid to Its tRNA

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Binding of an Amino Acid to Its tRNA

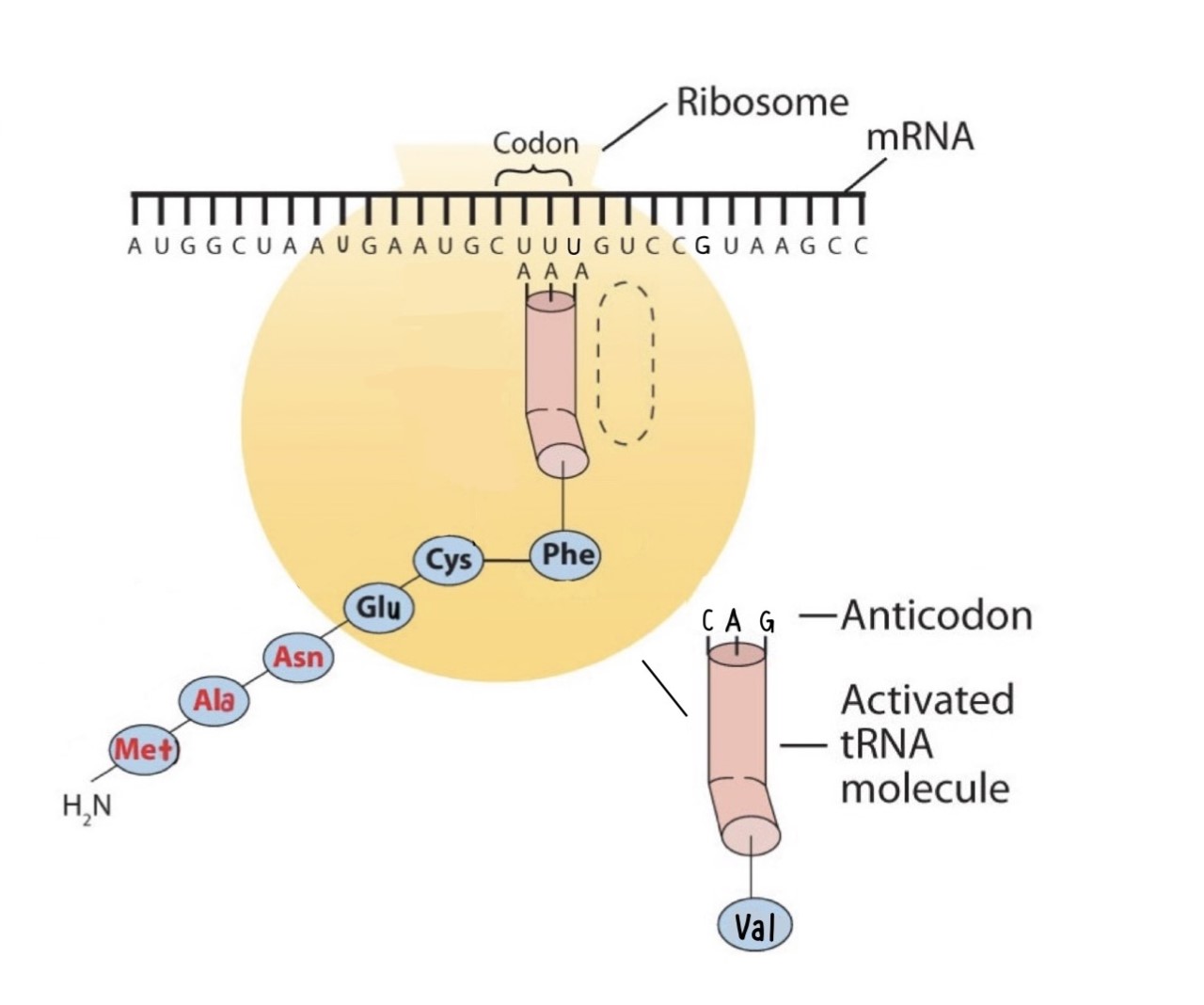

Before an amino acid can be incorporated into a polypeptide chain, it must be attached to its unique tRNA. This crucial process requires an enzyme known as aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). There is a specific aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase for each amino acid. This high degree of specificity is vital to the incorporation of the correct amino acid into a protein. After the amino acid molecule has been bound to its tRNA carrier, protein synthesis can take place. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) depicts a schematic stepwise representation of this all-important process.

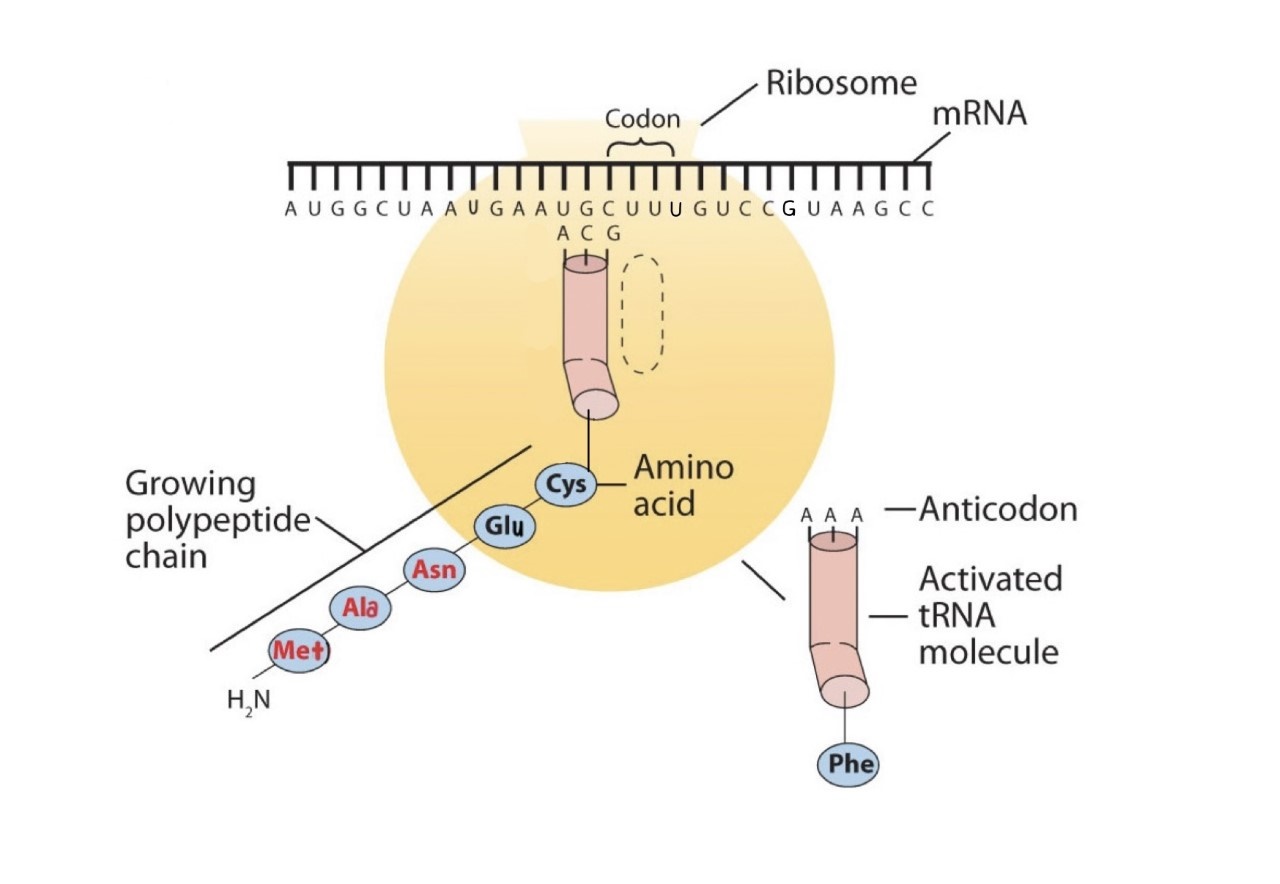

Figure \(\PageIndex{2a}\): The Elongation Steps in Protein Synthesis - Protein synthesis is already in progress at the ribosome. The growing polypeptide chain is attached to the tRNA that brought in the previous amino acid (in this illustration, cys.)

Figure \(\PageIndex{2a}\): The Elongation Steps in Protein Synthesis - Protein synthesis is already in progress at the ribosome. The growing polypeptide chain is attached to the tRNA that brought in the previous amino acid (in this illustration, cys.)

Figure \(\PageIndex{2b}\): The Elongation Steps in Protein Synthesis - An activated tRNA, which has the anticodon AAA, binds to the ribosome next to the previous bound tRNA and interacts with the mRNA molecule though basepairing of the codon and anticodon. The amino acid Phe is being incorporated into the polypeptide chain by the formation of a peptide linkage between the carboxyl group of Cys and the amino acid group of the Phe. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme peptidyl transferase, a component of the ribosome.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2b}\): The Elongation Steps in Protein Synthesis - An activated tRNA, which has the anticodon AAA, binds to the ribosome next to the previous bound tRNA and interacts with the mRNA molecule though basepairing of the codon and anticodon. The amino acid Phe is being incorporated into the polypeptide chain by the formation of a peptide linkage between the carboxyl group of Cys and the amino acid group of the Phe. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme peptidyl transferase, a component of the ribosome.

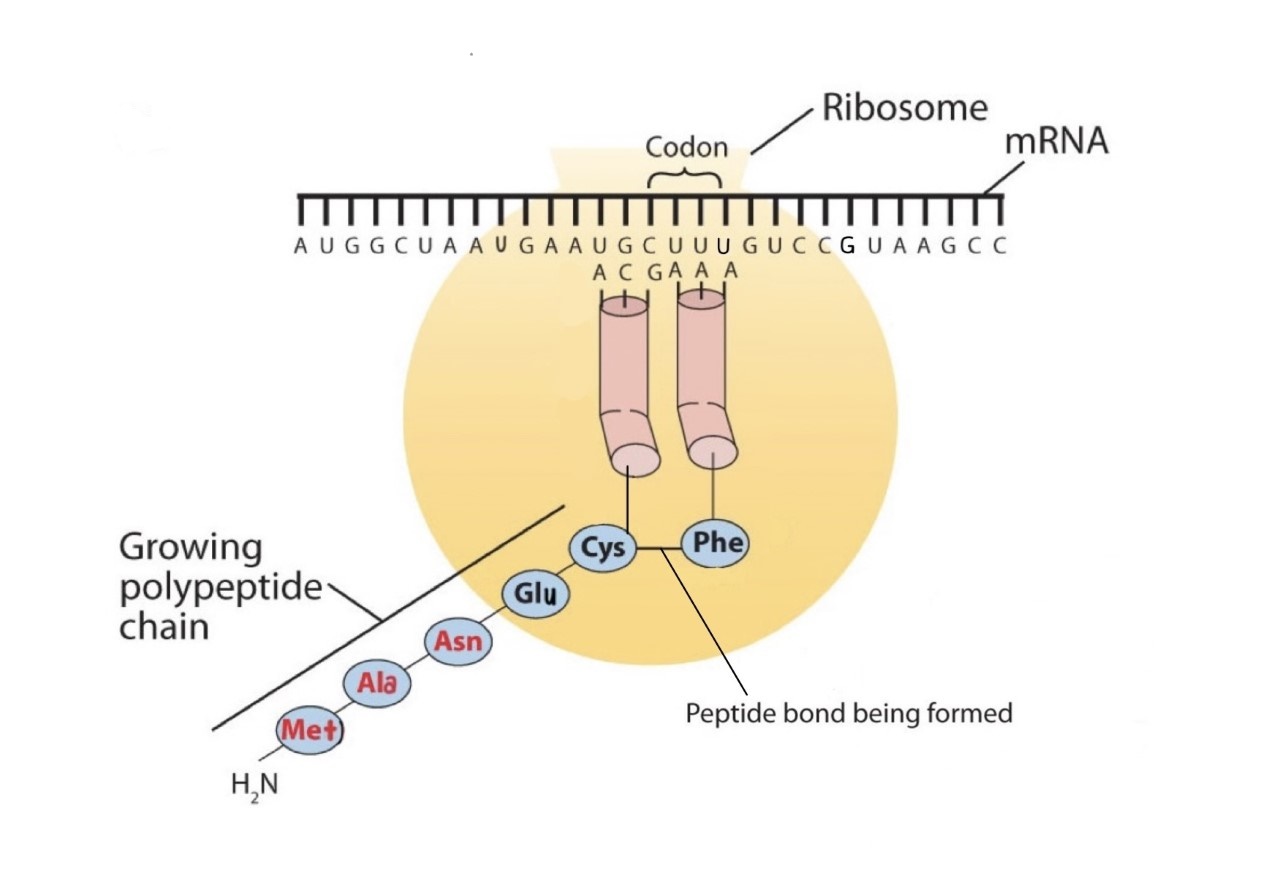

Figure \(\PageIndex{2c}\): The Elongation Steps in Protein Synthesis - The Cys-Phe linkage is now complete, and the growing polypeptide chain remains attached to the tRNA for Phe.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2c}\): The Elongation Steps in Protein Synthesis - The Cys-Phe linkage is now complete, and the growing polypeptide chain remains attached to the tRNA for Phe.

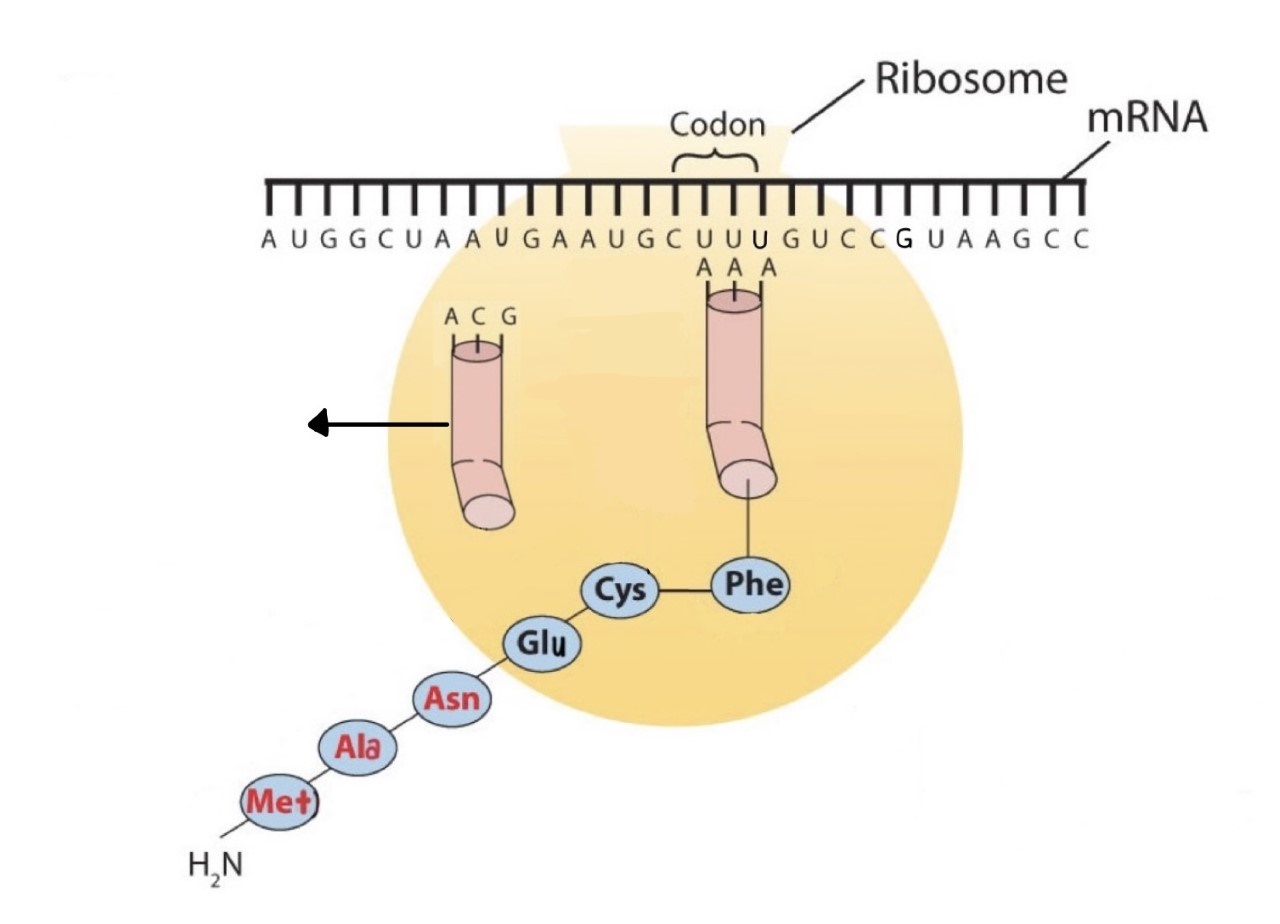

Figure \(\PageIndex{2d}\): The Elongation Steps in Protein Synthesis - The ribosome moves to the right along the mRNA strand. This shift brings the next codon, GUC, into its correct position on the surface of the ribosome. Note that an activated tRNA molecule, containing the next amino acid to be attached to the chain is moving to the ribosome. Steps (b)-(d) will be repeated until the ribosome reaches a stop codon.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2d}\): The Elongation Steps in Protein Synthesis - The ribosome moves to the right along the mRNA strand. This shift brings the next codon, GUC, into its correct position on the surface of the ribosome. Note that an activated tRNA molecule, containing the next amino acid to be attached to the chain is moving to the ribosome. Steps (b)-(d) will be repeated until the ribosome reaches a stop codon.

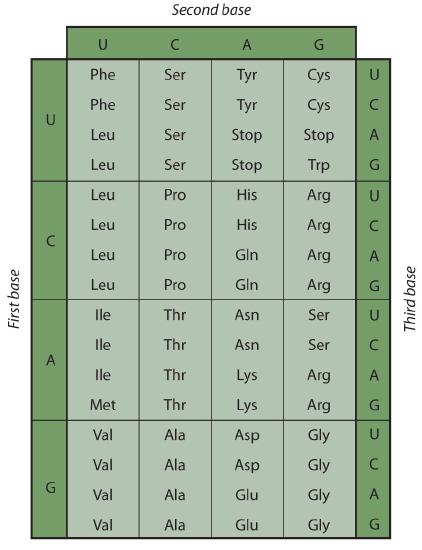

Early experimenters were faced with the task of determining which of the 64 possible codons stood for each of the 20 amino acids. The cracking of the genetic code was the joint accomplishment of several well-known geneticists—notably Har Khorana, Marshall Nirenberg, Philip Leder, and Severo Ochoa—from 1961 to 1964. The genetic dictionary they compiled, summarized in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), shows that 61 codons code for amino acids, and 3 codons serve as signals for the termination of polypeptide synthesis (much like the period at the end of a sentence). Notice that only methionine (AUG) and tryptophan (UGG) have single codons. All other amino acids have two or more codons.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): The Genetic Code

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): The Genetic Code

A portion of an mRNA molecule has the sequence 5′‑AUGCCACGAGUUGAC‑3′. What amino acid sequence does this code for?

Solution

Use Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) to determine what amino acid each set of three nucleotides (codon) codes for. Remember that the sequence is read starting from the 5′ end and that a protein is synthesized starting with the N-terminal amino acid. The sequence 5′‑AUGCCACGAGUUGAC‑3′ codes for met-pro-arg-val-asp.

A portion of an RNA molecule has the sequence 5′‑AUGCUGAAUUGCGUAGGA‑3′. What amino acid sequence does this code for?

Further experimentation threw much light on the nature of the genetic code, as follows:

- The code is virtually universal; animal, plant, and bacterial cells use the same codons to specify each amino acid (with a few exceptions).

- The code is “degenerate”; in all but two cases (methionine and tryptophan), more than one triplet codes for a given amino acid.

- The first two bases of each codon are most significant; the third base often varies. This suggests that a change in the third base by a mutation may still permit the correct incorporation of a given amino acid into a protein. The third base is sometimes called the “wobble” base.

- The code is continuous and nonoverlapping; there are no nucleotides between codons, and adjacent codons do not overlap.

- The three termination codons are read by special proteins called release factors, which signal the end of the translation process.

- The codon AUG codes for methionine and is also the initiation codon. Thus methionine is the first amino acid in each newly synthesized polypeptide. This first amino acid is usually removed enzymatically before the polypeptide chain is completed; the vast majority of polypeptides do not begin with methionine.

Summary

In translation, the information in mRNA directs the order of amino acids in protein synthesis. A set of three nucleotides (codon) codes for a specific amino acid.