5: Stress

- Page ID

- 74147

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Have you ever said to someone “I am so stressed out”?

If so, what were you stressed about?

How did you feel when you were stressed?

What did you do when you were feeling stressed?

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- Define Stress

- Assess your level of stress

- Describe the physiological reaction of the “fight or flight” response

- Recognize the effects of stress on well being

- Describe productive and counterproductive cognitive and behavioral stress responses

- Apply stress reducing strategies

WHAT IS STRESS?

Stress — just the word may be enough to set your nerves on edge. Everyone feels stressed from time to time. But, what does it mean when we say we have stress? And is all stress bad?

Stress is how the body reacts to a challenge or demand.

Stressor is something that causes stress. These could include natural disasters, big life changes, poverty or inequality, demanding jobs, relationships, or daily hassles like traffic.

Stress Response is how you respond to stress including physical, emotional, and behavioral responses. The bodies physical response to stress is termed the “Fight or Flight” reaction. Emotional responses might include feelings of anger, sadness, inability to focus, irritable, or anxiousness. Behavioral responses to stress might include sleep disturbances, aggression, avoiding the challenge, or use of drugs or alcohol.

A simple way to differentiate these terms is the following equation:

Stressor + Stress Response = Stress

Take a few minutes to think about times in your life where you were stressed.

Make a list of your stressors: What caused the stress? What challenge, demand, or situation triggered the stress?

Make a list of your common stress responses: How did you respond to the stress? Did you recognize physical changes in your body? Did you recognize emotional changes? Did you respond with positive or negative behaviors?Looking back on the times of stress, can you identify any opportunities you might have to change your responses that might have lowered the stress in your life?

Common Stressors

Stress may be recurring, short-term, or long-term and may include things like commuting to and from school or work every day, traveling for a yearly vacation, or moving to another home.

Common causes of short-term stress:

- Needing to do a lot in a short amount of time

- Having a lot of small problems in the same day, like getting stuck in traffic jam or running late

- Getting ready for a work or school presentation

- Having an argument

Common causes of long-term stress:

- Having problems at work or at home

- Having money problems

- Having a long-term illness

- Taking care of someone with an illness

- Dealing with the death of a loved one

Change is a leading cause of stress. Changes can be positive or negative, as well as real or perceived. Changes can be mild and relatively harmless, such as winning a race, watching a scary movie, or riding a rollercoaster. Some changes are major, such as marriage or divorce, serious illness, or a car accident. Other changes are extreme, such as exposure to violence, and can lead to traumatic stress reactions.

Physical Response: The Fight or Flight Response

Imagine how you would feel in the following situations:

- You are driving to school and you see an accident occur right in front of you! You swerve and avoid crashing into the cars.

- You just got a call from the police that something has happened to your family member.

- You are on a morning walk and an aggressive dog comes running toward you.

You might feel the following physical symptoms:

- Rapid heartbeat

- Sweaty palms

- Tense muscles or shaking

- Rapid breathing

- Nauseous

The symptoms you feel are a product of the bodies automatic physical reaction to stressors, called the Fight or Flight response. The Fight or Flight response is very important for our survival as it enables the body to take action quickly, and is intended to keep us out of (physical) harm’s way.

When a person senses that a situation demands action, the body responds by releasing chemicals into the blood. The hypothalamus signals the adrenal glands to release a surge of hormones that include adrenaline and cortisol. These stress hormones prepare the body to either fight off the stressor or flee from the stressor. Your heart rate increases to get more oxygenated blood to your muscles so you can prepare for action. Your breathing increases to get more oxygen. An increase in perspiration (sweating) keeps your body cool. These physiological effects are valuable when faced with a potentially dangerous situation.

Regardless of whether the stress experienced is negative or positive, small or extreme, the physical effects on the body are the same. For example, the stress hormones are produced whether you are stressed because of ongoing financial struggles or are stressed because you almost got in a bad car accident. Unfortunately, most of the stressors people face—work, school, finances, relationships—are a part of everyday life, and thus, inescapable. In modern life, we do not get the option of “flight” very often. We have to deal with those stressors all the time and find a solution. When you need to take an SAT test, there is no way for you to avoid it; sitting in the test room for five hours is the only choice. Lacking the “flight” option in stress-response process leads to higher stress levels in modern society. Living with constant stress that is constantly triggering a physical stress response can cause physical issues such as upset stomach, headaches, sleep problems, weight gain or loss, muscle aches, and heart disease.

Emotional and Behavioral Response

People respond to stress differently. For example, some people experience mainly digestive symptoms, while others may have headaches, sleeplessness, depressed mood, anger and irritability. Your emotional and behavioral responses to stressors in your life might include:

Psychological, emotional, or cognitive symptoms:

- Feeling heroic, euphoric or invulnerable

- Denial

- Anxiety or fear

- Worry about safety of self or others

- Irritability or anger

- Restlessness

- Sadness, moodiness, grief or depression

- Vivid or distressing dreams

- Guilt or “survivor guilt”

- Feeling overwhelmed, helpless or hopeless

- Feeling isolated, lost, lonely or abandoned

- Apathy

- Over identification with survivors

- Feeling misunderstood or unappreciated

- Memory problems/forgetfulness

- Disorientation

- Confusion

- Slowness in thinking, analyzing, or comprehending

- Difficulty calculating, setting priorities or making decisions

- Difficulty Concentrating

- Limited attention span

- Loss of objectivity

- Inability to stop thinking about the disaster or an incident

Behavioral or social symptoms:

- Change in activity levels

- Decreased efficiency and effectiveness

- Difficulty communicating

- Increased sense of humor/gallows humor

- Irritability, outbursts of anger, frequent arguments

- Inability to rest, relax, or let down

- Change in eating habits

- Change in sleep patterns

- Change in job performance

- Periods of crying

- Increased use of tobacco, alcohol, drugs, sugar or caffeine

- Hyper-vigilance about safety or the surrounding environment

- Avoidance of activities or places that trigger memories

- Accident prone

- Withdrawing or isolating from people

- Difficulty listening

- Difficulty sharing ideas

- Difficulty engaging in mutual problem solving

- Blaming

- Criticizing

- Intolerance of group process

- Difficulty in giving or accepting support or help

- Impatient with or disrespectful to others

After reading about common stressors and the stress responses, you might be interested in learning more about the stress in your life. A tool you can use to better understand your stress and your health is to take a Stress Self-Assessment. The following self-assessments are not used as a diagnosing tool, rather as a tool to help you become more self aware of stress you have so that you can make healthy lifestyle changes or seek medical assistance.

There are several Stress Self-Assessments available online, here are just a few:

STRESS AND DISEASE

The relationship between stress and health is complex. Each person perceives and responds to stress differently and there are different types of stresses, both good and bad. For some people, it happens before having to speak in public. For other people, it might be before a first date. What causes stress for you may not be stressful for someone else. With so much variation in stress, it is challenging to determine the exact relationship of stress and disease. However, since about the 1940’s scientists and researchers have been working to better understand the relationship.

People experience both eustress and distress. A person experiences eustress, also referred to as “good stress,” when the stressor helps the body enhance performance or overcome lethargy, it is their optimal level of stress. Distress, or what we view as “bad stress,” is when the body cannot cope with the stressor and leads to fatigue, or behavioral and physical problems. Stress can be helpful if it encourages you to meet a deadline or get things done. But feeling stressed for an extended amount of time can take a toll on your mental and physical health.

Optimal Stress

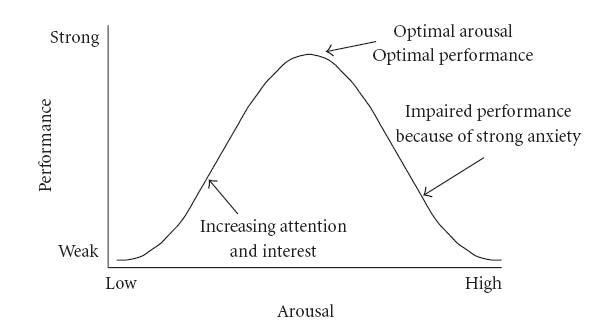

Although we tend to associate stress and health negatively, there is also a positive association between stress and health. Some stress can be good for you and help you to reach optimal performance. The relationship between stress and optimal performance is called the Yerkes–Dodson law, developed in 1908. Although this is called a law, it is actually a concept explaining that we need a certain amount of stress (arousal) to reach optimal (strong) performance. If we have too little stress or too much stress our performance will weaken. If we are under-aroused, we become bored and will seek out some sort of stimulation. On the other hand, if we are over-aroused, we will engage in behaviors to reduce our arousal/stress.

Most students have experienced this need to maintain optimal levels of arousal (stress) over the course of their academic career. Think about how much stress students experience toward the end of spring semester—they feel overwhelmed with work and yearn for the rest and relaxation of summer break. Their arousal/stress level may be too high. Once they finish the semester, however, it doesn’t take too long before they begin to feel bored; their arousal level is too low and their level of performance or productivity is also typically lower. Generally, by the time fall semester starts, many students are ready to return to school. This is an example of how the arousal theory works.

General Adaptation Syndrome

In the 1930’s a young medical student named Hans Selye became very interested in the relationship of stress and disease and for the next 50 years he systematically studied its relationship. One of his biggest contributions to the field of study was his development of the General Adaptation Syndrome. Selye found that there seemed to be a common or typical stress response pathway that people experienced when confronted with a stressor.

The pathway is simplified into three stages: Stage 1- Alarm, Stage 2- Resistance, and Stage 3- Exhaustion. This pathway begins when a person is exposed to a stressor and they are at first taken off guard and the body launches the Fight or Flight response (alarm stage). If the perceived stress continues, they attempt to maintain homeostasis by resisting the change (resistance stage). Our body wants to stay in homeostasis, which is a state of physiological calmness or balance, and occurs when our bodily functions are running smoothly in conjunction with low stress levels. Finally they eventually fall victim to exhaustion due to prolonged exposure to the stressor and depleting the bodies ability to cope to maintain homeostasis (exhaustion stage). Reaching the exhaustion stage leads to illness due to the resulting wear and tear on the body which leads to suppressing the immune system and causing bodily functions to deteriorate. This can lead to a variety of health issues and illnesses, including heart disease, digestive problems, depression, and diabetes.

For example, you just find out that you have to pass a certification test in 2 months in order to keep your job and have not started studying. Your first reaction might be shock, anger, feelings of hopelessness, or anxiousness. This is the first stage, the alarm stage. You could choose to quit your job and flee from the stress, however you know how important it is, so you make a plan to prepare the test and include deep breathing exercises. In this stage you are resisting the stress with coping mechanisms. As the certification test gets closer you once again begin feeling stress, you might feel like you are doomed to fail this test and feel desperate, feel constantly anxious, have difficulty falling asleep and waking up in the morning. This is the exhaustion stage and where you will be more susceptible to getting sick. The exhaustion of this stage will have deleterious effects on your health by depleting your body resources which are crucial for the maintenance of normal functions. Your immune system will be exhausted and function will be impaired.

Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI)

Unlike the Yerkes-Dodson Law or the General Adaptation Syndrome, Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) is not a model or framework, but rather a discipline of study. People who study the discipline of PNI study the relationship between the endocrine system, the nervous system, and the immune system to better understand the connection between the mind and the body.

For example, in the 19080’s a married couple, one a psychologist and the other an immunologist, began to become aware of the growing body of research in PNI and realized they had a unique opportunity to bring their disciplines and perspectives together to add to the research on the relationship of stress and disease[1]. Rather than continue with research using animals, as many had before them, they wanted to study the connection between stress and immunity under more natural circumstances. This began years of researching medical students before, during, and after taking a very stressful 3-day exam. They found that the stressful exam brought about a decline in the students’ Natural Killer cells, one of the main immune cells that fight off disease.

There is a wealth of research on how stress impacts immune functioning leading to the belief that every one of the hormones/transmitters secreted by these nervous system regions has been shown to have the potential, either in vivo or in vitro, to alter some aspect of immunity[2]. It has been found that chronic stress is an immunosuppressive, meaning that it suppresses the immune system not allowing the body to have an efficient and effective immune response. It is now well established that psychological factors, especially chronic stress, can lead to impairments in immune system functioning in both the young and older adults.

COPING WITH STRESS

We know that everyone has stress in their lives and a little stress may be helpful, but too much stress can lead to illness. It is important to recognize the stress in your life and then take action to handle stress in a positive way and keep it from making you sick.

Cognitive strategies to reduce stress

Cognitive strategies to reduce stress are focused on how you think. These strategies can help you to develop a new attitude in regards to stress in your life.

- Become a problem solver.

- Make a list of the things that cause you stress. From your list, figure out which problems you can solve now and which are beyond your control for the moment. From your list of problems that you can solve now, start with the little ones. Learn how to calmly look at a problem, think of possible solutions, and take action to solve the problem. Being able to solve small problems will give you confidence to tackle the big ones. And feeling confident that you can solve problems will go a long way to helping you feel less stressed.

- Be flexible.

- Sometimes, it’s not worth the stress to argue. Give in once in a while or meet people halfway.

- Get organized.

- Think ahead about how you’re going to spend your time. Write a to-do list. Figure out what’s most important to do and do those things first.

- Set limits.

- When it comes to things like work and family, figure out what you can really do. There are only so many hours in the day. Set limits for yourself and others. Don’t be afraid to say NO to requests for your time and energy.

- Set priorities

- Decide what must get done and what can wait, and learn to say no to new tasks if they are putting you into overload.

- Reward accomplishments

- Recognize what you have accomplished at the end of the day, not what you have been unable to do.

- Build your Resilience

- Resilience refers to the ability of an individual, family, organization, or community to cope with adversity and adapt to challenges or change. Everyone will experience hardships in life from everyday challenges to traumatic events and each person reacts to the challenges differently. Being resilient does not mean that a person does not experience difficulty or distress but it may help you adapt well over time to stressful situations.

- Resilience is the ability to:

- Bounce back

- Take on difficult challenges and still find meaning in life

- Respond positively to difficult situations

- Rise above adversity

- Cope when things look bleak

- Tap into hope

- Transform unfavorable situations into wisdom, insight, and compassion

- Endure

Relaxation Strategies to Reduce Stress

Taking time to relax is helpful response to stress in your life. There are many ways you can purposefully relax, here are a few techniques to try:

Stretch

Stretching can also help relax your muscles and make you feel less tense.

Get a Massage

Having someone massage the muscles in the back of your neck and upper back can help you feel less tense.

Do something you love

Take time to do something you want to do. We all have lots of things that we have to do. But often we don’t take the time to do the things that we really want to do. It could be listening to music, reading a good book, or going to a movie. Think of this as an order from your doctor, so you won’t feel guilty!

Practice Deep Breathing

When we become stressed, one of our body’s automatic reactions is shallow, rapid breathing which can increase our stress response. Taking deep, slow breaths is an antidote to stress and is one way we can “turn-off” our stress reaction and “turn-on” the relaxation response. Deep breathing is the foundation of many other relaxation exercises.

Deep breathing activity:

- Get into a comfortable position, either sitting or lying down.

- Put one hand on your stomach, just below your rib cage.

- Slowly breathe in through your nose. Your stomach should feel like rising and expanding outward.

- Exhale slowly through your mouth, emptying your lungs completely and letting your stomach fall.

- Repeat several times until you feel relaxed.

- Practice several times a day.

- Try this guided video for Deep Breathing

Use Guided Imagery

In guided imagery, you picture objects, scenes, or events that are associated with relaxation or calmness and attempt to produce a similar feeling in your body.

- Sit or lie down in a comfortable position, with eyes closed.

- Start by just taking a few deep breaths to help you relax.

- Picture a setting that is calm and peaceful. This could be a beach, a mountain setting, a meadow, or a scene that you choose.

- Imagine your scene, and try to add some detail. For example, is there a breeze? How does it feel? What do you smell? What does the sky look like? Is it clear, or are there clouds?

- It often helps to add a path to your scene. For example, as you enter the meadow, imagine a path leading you through the meadow to the trees on the other side. As you follow the path farther into the meadow you feel more and more relaxed.

- When you are deep into your scene and are feeling relaxed, take a few minutes to breathe slowly and feel the calm.

- Think of a simple word or sound that you can use in the future to help you return to this place. Then, when you are ready, slowly take yourself out of the scene and back to the present.

- Tell yourself that you will feel relaxed and refreshed and will bring your sense of calm with you.

- Count to 3, and open your eyes. Notice how you feel right now.

- Try this guided video for practicing Imagery

Practice Progressive Muscle Relaxation

In Progressive Muscle Relaxation you reduce muscular tension and negative feelings by learning how to relax and relieve the muscular tension. The key to the relaxation process is taking some deep breaths and then proceeding to tense, then relax a group of muscles in a systematic order.

- Sit in a comfortable position, with eyes closed. Take a few deep breaths, expanding your belly as you breathe air in and contracting it as you exhale.

- Begin at the top of your body, and go down. Start with your head, tensing your facial muscles, squeezing your eyes shut, puckering your mouth and clenching your jaw. Hold, then release and breathe.

- Tense as you lift your shoulders to your ears, hold, then release and breathe.

- Make a fist with your right hand, tighten the muscles in your lower and upper arm, hold, then release. Breathe in and out. Repeat with left hand.

- Concentrate on your back, squeezing shoulder blades together. Hold, then release. Breathe in and out.

- Suck in your stomach, hold, then release. Breath in and out.

- Clench your buttocks, hold, then release. Breathe in and out.

- Tighten your right hamstring, hold then release. Breathe in and out. Repeat with left hamstring.

- Flex your right calf, hold, then release. Breathe in and out. Repeat with left calf.

- Tighten toes on your right foot, hold, then release. Breathe in and out. Repeat with left foot.

- Yry this guided video for Progressive Muscle Relaxation

Practice Meditation

Meditation is about clearing your mind. There are many types of meditation, but most have four elements in common: a quiet location with as few distractions as possible; a specific, comfortable posture (sitting, lying down, walking, or in other positions); a focus of attention (a specially chosen word or set of words, an object, or the sensations of the breath); and an open attitude (letting distractions come and go naturally without judging them).

- Sit in a comfortable position, with eyes closed.

- Set a time limit such as five or 10 minutes.

- Notice how your body feels

- Focus on your breath. Follow the sensation of your breath as it goes in and as it goes out.

- Notice when your mind has wandered and simply return your attention back to your breath. It is normal for your mind to wander, just come back.

- When time is up, take a moment and notice any sounds in the environment. Notice how your body feels right now. Notice your thoughts and emotions. Show yourself kindness and appreciation.

- Try this guided video for 5 Minute Mindful Meditation to be more Calm

Behavioral Strategies to Reduce Stress

It is important to take care of your body, especially when you are experience a lot of stress in your life.

Listen to your body

Recognize signs of your body’s response to stress, such as difficulty sleeping, increased alcohol and other substance use, being easily angered, feeling depressed, and having low energy.

Get enough sleep

Getting enough sleep helps you recover from the stresses of the day. Also, being well-rested helps you think better so that you are prepared to handle problems as they come up. Most adults need 7 to 9 hours of sleep a night to feel rested.

Eat right

Try to fuel up with fruits, vegetables, beans, and whole grains. Don’t be fooled by the jolt you get from caffeine or high-sugar snack foods. Your energy will wear off, and you could wind up feeling more tired than you did before.

Get moving

Getting physical activity can not only help relax your tense muscles but improve your mood. Research shows that physical activity can help relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Avoid counterproductive actions

Don’t deal with stress in unhealthy ways. This includes drinking too much alcohol, using drugs, smoking, or overeating.

Explore stress coping programs, which may incorporate meditation, yoga, tai chi, or other gentle exercises.

Social Strategies to Reduce Stress

Connecting with others is a helpful strategy for stress reduction.

Share your stress

Talking about your problems with friends or family members can sometimes help you feel better. They might also help you see your problems in a new way and suggest solutions that you hadn’t thought of.

Get help from a professional if you need it

If you feel that you can no longer cope, talk to your doctor. She or he may suggest counseling to help you learn better ways to deal with stress. Your doctor may also prescribe medicines, such as antidepressants or sleep aids. Get proper health care for existing or new health problems.

Help others

Volunteering in your community can help you make new friends and feel better about yourself.

You can reduce stress in 10-15 minutes with one of the following activities:

- Get outside. Take a nature walk or city hike. Remember to wear a mask and stay 6 feet from others.

- Take a dance break!

- Write three things you are grateful for today.

- Giving back to others can help you too. Take a look at volunteer opportunities that interest you through a site such as VolunteerMatch.

- Take a break from the news today… watch or listen to something fun.

- Wash your face or rinse your hands in cool water to reduce tension and calm nerves.

- Check in with a friend, family member or neighbor. Talk by phone, video chat or visit in person while maintaining proper distance and wearing masks.

- Close your eyes, take deep breaths, stretch or meditate.

- Laugh! Think of someone who makes you laugh or the last time you laughed so hard you cried.

- Channel your energy into a quick cleaning of your home.

- Exercise. Lift weights. Do push-ups or sit-ups. Kick around a soccer ball.

- Make and enjoy a cup of tea and relax in a comfortable place.

- Consider a new hobby, such as playing a musical instrument, gardening, trying a new recipe, working on a crossword puzzle or knitting.

- Connect with your faith through prayer or reach out to a member of your faith community.

- If you’ve been feeling overwhelmed with stress, anxiety, sadness or depressed mood, use this time to make an appointment with a counselor.

- Check in with yourself—take time to ask yourself how you are feeling.

- Curl up with a book or magazine in a comfortable place.

- Practice relaxation exercises or yoga.

- Find an inspiring song or quote and write it down (or screenshot it) so you have it nearby.

Key Takeaways for Chapter 5

- Stressor is something in your life that causes stress.

- The Stress response is your physical, emotional, and behavioral response to stressors.

- Stressor + Stress Response = Stress

- The fight or flight response is the bodies physical response to stressors

- The fight or flight response is very important for escaping danger, however is elicited at any level of stress, either acute or long term.

- People have varying emotional and behavioral responses to stress.

- It is important to use productive behavioral responses rather than counter-productive responses.

- Some stress is good for you!

- Too much negative stress is associated with disease.

- You can take purposeful actions to reduce stress in your life.

Media Attributions

- HebbianYerkesDodson © Yerkes and Dodson, Hebbian is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K., & Glaser, R. (1993). Mind and immunity. In: D. Goleman & J. Gurin, (Eds.) Mind/Body Medicine (pp. 39-59). New York: Consumer Reports. retrieved from http://pni.osumc.edu/pnimedstudent.html. ↵

- Tausk, F., Elenkov, I. and Moynihan, J. (2008), Psychoneuroimmunology. Dermatologic Therapy, 21: 22-31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00166.x ↵